Backcountry Journal: “All the Right Words”

Wind howled through the canyon like a locomotive, snapping fire-blackened aspens and leaving a graveyard of widow-makers and deadfall in its wake. When we set camp, I had been excited to use my new tipi tent – the kind with the three-hands-required-for-assembly wood stove.

Now I was going to die in this tent.

I looked over at Ronan – a friend I was deployed with twice overseas – for solidarity in our final moments before being pulverized by whatever angry mountain god was responsible for this cacophony of exploding tree trunks and flying splinters.

He was asleep. That son of a bitch.

Alone with the demons, I crawled deeper into my bag and waited.

Hermosa Creek Wilderness Area sits within the San Juan National Forest, just north of Durango, Colorado. I picked that spot because it had all the right words – wilderness, Colorado and Durango. I always wanted to be in a Western. It’s more than 37 thousand acres of hog-backed ridges and incredible drop-offs, which was where I was headed if I couldn’t figure out a way to clear my head.

2020 had been a bad year. Not because of the pandemic, though that was part of it.

In some far-off place on the ragged edge of the empire, my new year rang in with fireworks and a light show. Only, the fireworks were rocket-propelled grenades and mortars. The light show was enemy tracers snapping past with a distinctive “crack” – the kind every U.S. Marine recognizes from working pits at the rifle range.

A year later, I couldn’t get the boom out of my head.

To make matters worse, I lost my team to the confusion of redeployment home amid the chaos of the pandemic’s early days. By the time we figured out that covid was bad, but not zombie apocalypse bad, we had been working remote for six weeks. Then, I was transferred to another unit. It felt like getting ripped out of bed in the middle of the night and forced under the covers with someone else’s wife.

I felt as though I was imploding. I needed space to get away from the pressure and return to my true form. I needed space to think.

Wilderness. Colorado. Durango. All the right words.

We hunted elk as though they were hunting us. It was both strange and familiar.

As the military saying goes, “Two is one, and one is none.” I needed a wingman. Immediately, I thought of my friend Ronan. He was not a hunter. He neither caught fish nor fired guns outside of the military, but he was a man after my own heart.

The first time we ever did anything together, a miscommunication put us on opposite sides of the same mountain. Each thought the other ditched at the last minute, so we attacked separate routes – only to run into one another at the summit. I knew he would meet me at the top of whatever mountain we needed to climb.

I was raised in the woods. I grew up a houndsman, deer hunter and waterfowler. Training for war in the swamps of the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, felt like another racoon hunt – just more serious. As if the raccoons had guns and deadly intent. But the world of Western hunting was new and my depth of research consisted of a couple episodes of MeatEater. Naively, I figured, “If that guy could do it. …”

The day before getting to Durango, the day before sliding from one type of abyss into another, I picked up Ronan from a small airport in northern New Mexico. He had just completed military free-fall parachute training, which made him “sky trash.” I could still smell the wind and terminal velocity on his clothes when he got in the truck. Everywhere he went you could hear Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” in the background. He was the high to my low. Balance.

After a dark journey through the country, which I am certain was beautiful in the daylight, we pulled up the long dirt road to our predetermined parking area about 0400. Along the way we passed a small parking lot with a wall tent and three pickups. I, however, was headed for the end of the road.

We were greeted by a full-blown outfitter camp. Horses, wall-tents, rifles and coffee were everywhere. Guides were packing mules for the ride in, and hunters were lazily finishing up their bacon and eggs. It looked like heaven. We must have looked like a couple of sinners strolling through the pearly gates. That’s the reception we got, anyhow.

A man similar to Saint Peter, mounted atop his high horse and waving his hand in a 360-degree circle, looked down at us and said, “You boys need to get out of here. We lease the hunting rights from the Forest Service for this whole area. All you had to do was call and ask.”

“We’re just trying to get to public land,” I told him, incredulous that anyone could lease exclusive hunting access to a federally designated wilderness area.

I began to lay out Forest Service maps on the tailgate, listening to “All you had to do was call and ask,” being repeated over and over while trying to figure a solution to our problem. That’s when the weather solved it for us.

A tall man with a long, gray beard walked over to “Saint Pete” and said, “Forecast looks bad, Steve. We need to get out of here before it gets worse.” Despite his small stature and cantankerous nature, I could tell that Steve was in charge and had a tough decision to make. I understood the predicament.

After a few hand gestures and another, “All you had to do was call and ask,” we headed back to the lot with the pickups and wall tent. We should have kept driving – all the way back to town.

That’s what “Saint Steve” and his horse wranglers did a few minutes later.

By 0500, they packed up heaven and left us in hell. We just didn’t know it yet. We didn’t know hell was cold, either. It was about to freeze over.

Watching “Steve the Apostle” and his entourage snake their way down the mountain, Ronan and I rucked up and walked back to where the outfitter camp had been. Smoldering ashes dumped from a wood stove and a few steaming piles of horse shit were all that was left. It was a ghost camp. That’s when it began to snow.

With the swirl around us, Ronan and I started walking. I’d never hunted elk, and he’d never hunted at all, so we defaulted to our common baseline experience – patrolling. We walked like we were in the film, “The Hills Have Eyes.” Elk eyes.

We crested each ridge with the same ceremony granted to Richard Connell’s short story, “The Most Dangerous Game.” Each man moves to the flanks, head up, rifle at the ready. Unless contact is imminent, the rifles are swapped for glass as the observers scan, by quadrant, the opposing hillsides as they come into view. Nothing. Map check and continue to move. We hunted elk as though they were hunting us. It was both strange and familiar.

We barely spoke all day – our communication done with gestures and hand-signals. Once, seeing a cow elk at the edge of the burn we entered, we practiced our setup and shot sequence, crawling up to the ridgeline, placing rucks out front as rifle rests and getting the spotter positioned to observe the shot. But with only a bull tag, we painstakingly reversed the process and left her to graze, undisturbed.

We moved that way for the rest of the day, cutting cross-country and deeper into the burn. For mile after jagged mile, the charred and blackened remains of what once was a forest rose like specters around us. We were alone, walking among them, living in the presence of the dead.

Our first day ended in that canyon bottom, a place I thought would shelter us from the wind. A creek ran alongside, and the remains of another outfitter camp stood nearby with rings of river rocks marking the graves of campfires past. I took them for sign that this was as good a spot as any to set a spike camp. With water replenished and a warm meal in our bellies, we took shelter for the night, a thin layer of polyester and nylon encapsulating us from the accumulation building outside. That’s when the wind truly began to blow.

In the summer of 2018, two years before we found ourselves encamped in the desolation of that canyon, a pair of wildfires converged on the Hermosa Creek Wilderness. What’s known as the 416 Fire came from the east, ignited by embers from a coal-fueled passenger train, becoming the sixth largest wildfire in Colorado history. The Burro Fire came from the west, source undetermined.

Most fires build resiliency in forest ecosystems. With the underbrush gone and pathways for sunlight open to the forest floor, new growth and sources of sustenance are created. But if a fire gets too hot and if too much time passes without nurturing the flame, fuel sources build, heat burns through bark and cambium, soil becomes unstable and the forest dies.

From opposing sides of the same mountain, the 416 and Burro fires attacked their separate routes – running into one another in the abyss of that canyon. At their confluence, the combined heat built to the level of inferno, and they killed the forest.

We knew none of that at the time.

How does one field dress, with words, the complexities of war, guilt and responsibility?

How can you give a voice to that which drives men to seek shelter in the wilderness?

What spell must be spoken to dislodge what lurks in the unswept corners of the mind?

The wind grew to hurricane force. Like a wraith enraged by the sentience of our presence, it howled over the broken bones of a dead landscape. The groan of falling trees built to a Shepherd’s tone and each gust sounded the swing of snath and scythe. Skeletons of trees began to fall, halved at their shins. The rattling of bones drew nearer, joints exploding under the weight of an unseen menace. With each swing of the reaper’s blade, each shatter of wood and sanity, the squall intensified. The walls closed in around us and drifts of snow pressed against our bodies through the tent walls.

And then it passed.

The dawn brought a scene almost surreal. Under the rising sun, the corpses of wind-felled trees were arranged like a dry-ground replica of old museum photos from the logging boom – the ones in which a thousand timbers float down an impossible rapid, young men with axes precariously perched on the pinnacle of their accomplishment. And right in the middle of that river was our tent. Fire and wind had distorted the reality of the mountain.

The deeper truth? Maybe it was that “shit happens” – and sometimes you survive.

The deeper truth? Maybe it was that “shit happens” – and sometimes you survive.

Whatever the lesson, we needed to get out of that canyon. Altitude sickness set in. I was losing weight from both ends. Ronan, having just spent six weeks at 13 thousand feet – at least until the light turned green and he jumped – remained unaffected. He out-hiked me to the point of embarrassment.

When he offered to share the load, I was slumped into a snow drift, my pants around my ankles and head between my knees.

“This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine,” I told him. I held my rifle like the last vestige of dignity that it was. I’d as soon die as hand it over. I let him carry the tripod, but we don’t talk about the tripod.

We wanted out, but the mountain opposed us, positioning the twin impediments of deadfall and snowdrift like an abatis. And so, as the hours dragged on, I accepted the gift of time and pondered, “Wasn’t this why I’d come to this place? The place with all the right words?”

What are those words, “the right ones?” How does one field dress, with words, the complexities of war, guilt and responsibility? How can you give a voice to that which drives men to seek shelter in the wilderness? What spell must be spoken to dislodge what lurks in the unswept corners of the mind?

At some point, we navigated the last obstacle and broke into open country. The wind-swept and ash-strewn landscape gave way to an expansive wilderness studded with life. We stopped to rest and refit.

Whether from altitude sickness or a deeper struggle I do not know – my insides desperately wanted to become my outsides. I did the one thing known to conjure opportunity at the worst moment – I stepped behind a bush and dropped my drawers.

“Elk!” yelled Ronan. Push, wipe, bury.

Yellow forms crested the ridge a mile to the east and one by one dropped into a south-facing meadow. Two bulls, one much larger than the other, trailed a herd of 30 cows.

We ran to beat the sunset. Wind at their backs and sun in their eyes, the elk didn’t notice the two forms moving to intercept them. We dropped rucks and checked the range – 500 yards on the nose, which is qualifying distance on the rifle range.

The rifle barked, and the larger of the two bulls flinched as he looked for the source of discomfort. The distance, wind and terrain made locating us impossible, and the herd stood like statues in the meadow. Three more shots and the bull dropped in place – exactly where he stood when I began firing seconds before. When we reached him, four entry wounds pockmarked a softball-sized space behind his shoulder, exiting from what appeared to be the same hole on his opposite side.

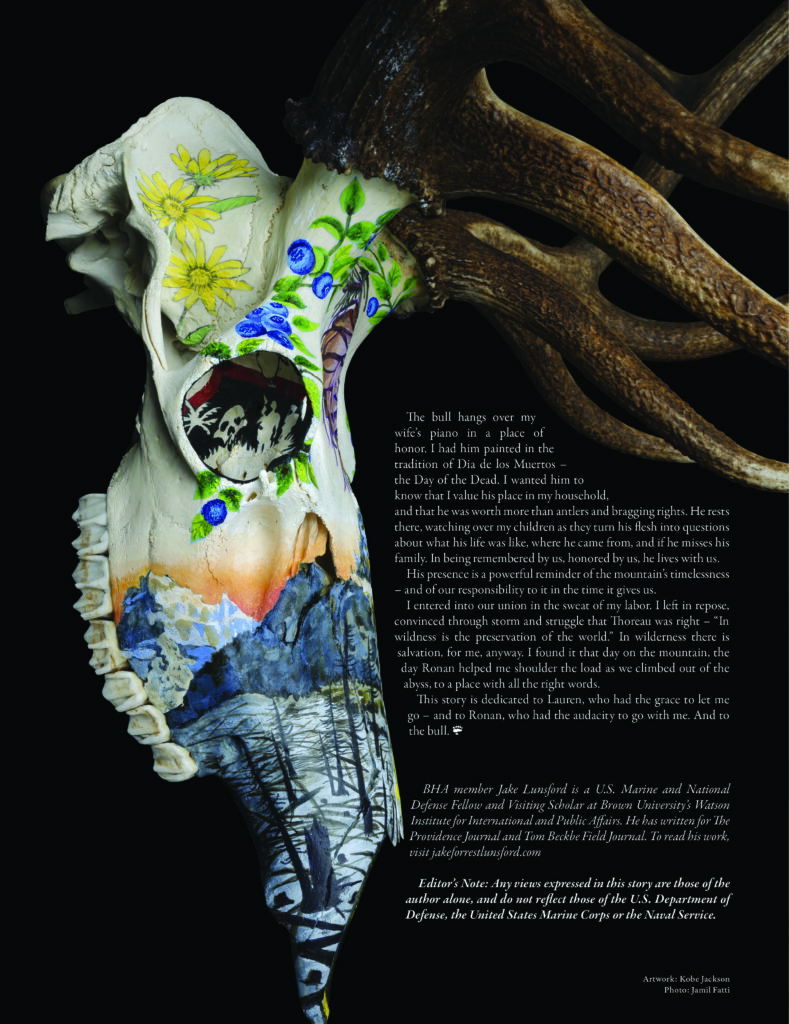

The next day’s pack-out took 10 hours, and we reveled in the brutality of it. That night, at a roadside café on U.S. Route 160, I cut a piece of cake and gave it to Ronan in celebration. The date was Nov. 10, 2020 – the 245th birthday of the United States Marine Corps.